2.24.2013

2.21.2013

A Guy on Facebook

Is it creepy to write a blog post about somebody's Facebook statuses? Probably.

A guy from my high school recently joined Facebook:

I think we went to school together all the way from Kindergarten to senior year, but I could be wrong about that. One time, in Chemistry class, I remember talking to him and this other guy. I forget how I contributed to the conversation, but the other guy said that he had twelve teeth pulled at one time and this guy (our new Fbook guy) told us that he had technically died three times, and that doctors had to bring him back to life. (And I think he was telling the truth; he had had a childhood illness or something. Or maybe it was somebody else who went to my high school... but I think it was him. I remember being impressed.)

He followed up that post with one that said, "I hope you are ready for a long rambling explanation of who and where I am at." And he includes a long rambling explanation about his height and weight, what he does, what he likes, how he's had problems with dating, how he's unhappy ("I really should shut up and be happy. Instead I fret over stupid shit."), how he doesn't know what to do about it, and he ends with "and the worst part is I feel like this was the short version."

Facebook is generally a place where we advertise ourselves. We don't even take pictures anymore; we shoot ads. I'm happy. I'm playful. I'm in love. I go places. I have lots of friends.

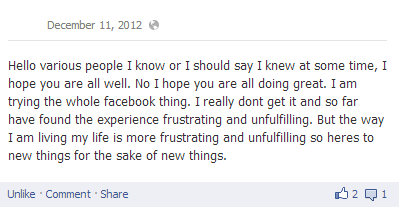

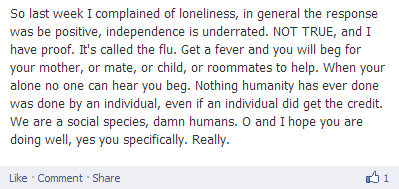

This guy writes things like this:

and

He talks about all the areas where he thinks he's failing. He calls himself an asshole. He says way too much about his love life, for my taste. He's, like, terrible at marketing.

It could be entirely a persona that he's putting on. Nobody says there is necessarily truth or a lack of manipulation in his "realness." Still, it makes me excited (and sometimes uncomfortable) to see something like it on Facebook. He cannot be the only person in their mid-twenties who feels like they are screwing it all up, like their chances at happiness and actualization are shot. I feel like that. I really feel that.

People talk about "internet communities," and they seem like a great idea, to me, if they can be accomplished. My friends are scattered all over the country (and a few internationally); it's hard to meet new people - to actually connect with people. If the internet was an adequate place for social interaction, it could be great news to lots of folks. And I feel like that sort of community could be possible, if everybody was more like this guy. If people gave you something, on the internet, to connect to. We could all get online and share our humanity.

But that will never happen. I don't think it's how people work. We want too badly to look good, and anyway, the internet is not a safe enough environment for that.

The majority of people's comments to him have been some variation on "be more positive," "you'll find somebody," etc. And I think that the longer he's on Facebook, the more positive his posts will become. The more he'll start to sound like everybody else.

A guy from my high school recently joined Facebook:

I think we went to school together all the way from Kindergarten to senior year, but I could be wrong about that. One time, in Chemistry class, I remember talking to him and this other guy. I forget how I contributed to the conversation, but the other guy said that he had twelve teeth pulled at one time and this guy (our new Fbook guy) told us that he had technically died three times, and that doctors had to bring him back to life. (And I think he was telling the truth; he had had a childhood illness or something. Or maybe it was somebody else who went to my high school... but I think it was him. I remember being impressed.)

He followed up that post with one that said, "I hope you are ready for a long rambling explanation of who and where I am at." And he includes a long rambling explanation about his height and weight, what he does, what he likes, how he's had problems with dating, how he's unhappy ("I really should shut up and be happy. Instead I fret over stupid shit."), how he doesn't know what to do about it, and he ends with "and the worst part is I feel like this was the short version."

Facebook is generally a place where we advertise ourselves. We don't even take pictures anymore; we shoot ads. I'm happy. I'm playful. I'm in love. I go places. I have lots of friends.

This guy writes things like this:

and

It could be entirely a persona that he's putting on. Nobody says there is necessarily truth or a lack of manipulation in his "realness." Still, it makes me excited (and sometimes uncomfortable) to see something like it on Facebook. He cannot be the only person in their mid-twenties who feels like they are screwing it all up, like their chances at happiness and actualization are shot. I feel like that. I really feel that.

People talk about "internet communities," and they seem like a great idea, to me, if they can be accomplished. My friends are scattered all over the country (and a few internationally); it's hard to meet new people - to actually connect with people. If the internet was an adequate place for social interaction, it could be great news to lots of folks. And I feel like that sort of community could be possible, if everybody was more like this guy. If people gave you something, on the internet, to connect to. We could all get online and share our humanity.

But that will never happen. I don't think it's how people work. We want too badly to look good, and anyway, the internet is not a safe enough environment for that.

The majority of people's comments to him have been some variation on "be more positive," "you'll find somebody," etc. And I think that the longer he's on Facebook, the more positive his posts will become. The more he'll start to sound like everybody else.

2.19.2013

Land and Water

Since I went to college in Spokane, Washington (at a school where a strangely large number of Coloradans chose to attend) in the eastern/inland part of the state, I had the unfortunate experience of commonly hearing the mountain vs. water conversation.

Seattle/Puget Sound people were in the "water" category - a.k.a "I cannot live in a place without water - and there were a ton of them. And the Coloradans would home-sickenly fly their state flags and make fun of Pacific Northwestern topography (except for Mt. Ranier, which, technically, is a volcano, and you can never really see anyway). They were the mountain people.

I am from Colorado, and, admittedly, Colorado does not have water. I've been to the biggest lake in Colorado. It's not that big. It's beautiful, but it's made from glaciers, and is super cold even in the summer, and is far away from everything.

Now I live and work by Lake Michigan, and I'd tell you how many times bigger it is than Grand Lake (that one in Colorado), but I don't feel like calculating it because Wikipedia gives Grand Lake in terms of acres and Lake Michigan in terms of square miles. Mitch and I live three blocks away from the beach, and my desk at work overlooks the lake and Navy Pier. I run by the lake for exercise. I walk out there when I talk to my friends on the phone.

Even my commute is right along the there. After doing this for over a year, I have spent a lot of time with that lake.

And I was thinking, today, on my way home, that I don't know how those water people do it. Lake Michigan is beautiful and fantastic. I love it, but I don't know how one emotionally connects to water. The thing with mountains is that you come to know their profiles, their scars, their outlines against the sky. You become familiar with all these distinct and static markers; it's almost like knowing a person's face.*

That Lake always changes, though. It looks one way with the sun behind it in the morning, red and misty. It freezes in big veinous patterns in the winter. Sometimes, it blends in perfectly with the sky. There's nothing to memorize. Nothing is fixed.

And while beautiful, it seems, to me, alien, like there's nothing for me to connect to. And I think, maybe this will change, for me, in a couple of years.

*For our friends in South Dakota, especially.

Seattle/Puget Sound people were in the "water" category - a.k.a "I cannot live in a place without water - and there were a ton of them. And the Coloradans would home-sickenly fly their state flags and make fun of Pacific Northwestern topography (except for Mt. Ranier, which, technically, is a volcano, and you can never really see anyway). They were the mountain people.

I am from Colorado, and, admittedly, Colorado does not have water. I've been to the biggest lake in Colorado. It's not that big. It's beautiful, but it's made from glaciers, and is super cold even in the summer, and is far away from everything.

Now I live and work by Lake Michigan, and I'd tell you how many times bigger it is than Grand Lake (that one in Colorado), but I don't feel like calculating it because Wikipedia gives Grand Lake in terms of acres and Lake Michigan in terms of square miles. Mitch and I live three blocks away from the beach, and my desk at work overlooks the lake and Navy Pier. I run by the lake for exercise. I walk out there when I talk to my friends on the phone.

Even my commute is right along the there. After doing this for over a year, I have spent a lot of time with that lake.

And I was thinking, today, on my way home, that I don't know how those water people do it. Lake Michigan is beautiful and fantastic. I love it, but I don't know how one emotionally connects to water. The thing with mountains is that you come to know their profiles, their scars, their outlines against the sky. You become familiar with all these distinct and static markers; it's almost like knowing a person's face.*

That Lake always changes, though. It looks one way with the sun behind it in the morning, red and misty. It freezes in big veinous patterns in the winter. Sometimes, it blends in perfectly with the sky. There's nothing to memorize. Nothing is fixed.

And while beautiful, it seems, to me, alien, like there's nothing for me to connect to. And I think, maybe this will change, for me, in a couple of years.

*For our friends in South Dakota, especially.

2.17.2013

Fatalism in Oedipus Rex

I read this lecture-turned-web-essay on the play Oedipus Rex** by a professor at Vancouver Island University. I was taking a class on Greek Tragedy, at the time, that was fairly light, academically, and I found the essay while I was milling about after further Oedipal commentary. It's not the most astoundingly written essay, but the ideas in it are great (which is what I hope you'll end up saying about this blog post).

[**Oedipus Rex, in brief:

* King and Queen of Thebes receive prophecy that their newborn son will one day kill his father and marry his mother. They, therefore, give the baby to a shepherd and instruct the shepherd to leave the baby on a hillside to die.

* The shepherd has pity on the baby, and instead, he gives him to another shepherd to take him far away.

* This other shepherd is from Corinth and, luckily (sort of), the King and Queen of Corinth haven't been able to have children. So the shepherd gives the baby to the King and Queen of Corinth. They name him Oedipus because the baby's feet had been bound by K. & Q. of Thebes. Oedipus means "sore feet."

* Oedipus grows up and receives a prophecy that he will kill his father and marry his mother. Believing that the K. & Q. of Corinth are his parents, he flees in order to subvert the prophecy.

* While on the road, he gets in a tussle with some other travelers, and he kills all of them (except for one guy). The travelers happened to be K. of Thebes, Oedipus's father, and his men. Whoops.

* Oedipus arrives at Thebes! Where they have a pestilence brought on by a sphinx asking riddles. Oedipus answers the riddle, and the people of Thebes are so happy that they make him king. He marries the Queen of Thebes who is also his mother. (In all the film clips that I saw in class, Queen Jocasta (of Thebes) was a babe. So really, who could blame our guy?)

* Eventually, there's another pestilence, and this time it's brought on because nobody has been brought to justice for the murder of the King of Thebes. Oedipus is so confident and so upset and such a good king in general, that he promises that the murderer of King Laius will be found out and either killed or exiled.

* So then Oedipus uncovers that he himself is actually the murderer and finds out who his real parents are, and Queen Jocasta hangs herself, and Oedipus takes the broaches from the dress of her hanging body and gouges out his eyes. Then he wanders in the wilderness with his daughter.

* The end.]

When we read the play in my high school English class, the take-away message from it was that Oedipus was too proud and therefore fell from greatness. I didn't like the play because it felt pointlessly unfair. There was interesting irony, sure, and there was supposedly some catharsis I was supposed to feel and benefit from, but Oedipus was such a mistreated character. And we have the saying "pride comes before a fall," so why go through all the effort of writing a play and then centuries later teaching it to ninth graders? Plus, Oedipus's situation was too unique for it to effectively warn me away from head-puffing.

But, here's the thing: Sophocles wrote and set the play in a time where people believed in a fatalistic universe. A fatalistic universe is one in which "fates" or superhuman personalities control the rules and events of our lives according to their own principles. Depending on the culture or story, the fates may or may not have human forms or attributes. So, for example, in a lot of Greek myths the fates do have human forms and attributes and are presented as the gods Zeus, Athena, Apollo, and so forth. In Sophocles's tragedies, fate tends to be nameless and faceless.

Another example(s) of a fatalistic universe would be the Old Testament; fate in this context is God, who, depending on the story might be so human-like that he walks on Earth, or he might, very adamantly, not be described with any human characteristics.

Actually, according to this lecture/essay pretty much every story up until the eighteenth century holds a fatalistic view of life.

This is markedly different than how we think (mostly) anymore. Contemporary Western-Civ Americans believe that an individual's choices and actions determine the events in his or her life. (I say mostly because I think sometimes American Christians (and I mean some American Christians, not everybody) get stuck on the fatalistic vs. self-deterministic fence. They set a lot of store in the fatalist-'verse Bible, but can be very linked in to 'Merica. So, they believe that God has control of all the events in their lives, down to the parking spot they find in front of their work in the morning, and they also believe that they have to make certain choices because they determine whether or not they go to heaven.)

This understanding, that we as individuals are largely in control of the outcome and events of our lives, can lead to more didactic story-telling and story-reading, I think. Because if something bad happens to a character, we believe that we should be able to trace back into his history to find where he made a mistake or be able to point to a quality within him that caused his external suffering. Reading Oedipus like this makes it a really dull play.

But - but! - what about accepting a basic premise of the play, that no one can escape his fate? The lecture/essay points out that if it weren't for Oedipus's pride and temper, he wouldn't have a height to fall from. The things we point to as his modern "flaws" are what make him such a great king in the first place - he's very confident; he has strength of purpose; he's unwilling to compromise himself or his people. (I think he's a great guy.)

He suffers because he pits his will against fate. He refuses to compromise and change; he stands out and is isolated from society even while he is very successful in its context. He's a hero because in his suffering we recognize the strength of humanity, especially because he isn't rewarded, especially because he doesn't win. In a fatalistic culture, there was never a chance of his winning against fate, and yet in his suffering and death he becomes sort of immortal (hence, the teaching his story to twenty-first century teens), and maybe ranks as high as fate itself. So while everything, plot-wise, goes to absolute pot, there's a sense of triumph buried under all that suffering.

[A note on comedies (in the Shakespearian sense): the inverse of the suffering/triumph tension in tragedies is the happiness/loss tension in comedies. Comedies, those ones that start in conflict and end in marriage, are about affirming communities more than elevating individuals. (Example: the names of Shakespeare's comedies are things like "Much Ado About Nothing," "Midsummer Night's Dream," "Twelfth Night," "Love's Labor's Lost" while his tragedies are: "Macbeth," "Hamlet," "Julius Caesar," "Romeo and Juliet.") But while everybody tends to wind up in relative comfort, they have changed and made compromises over the course of the story. In order to thrive within the community, they have had to accept their fate. They have had to compromise some or most of their individuality. I attribute this as the reason, at the end of RomComs, I feel a little empty or sad even though all of the characters seem happy.]

It's got me thinking about our ideas about a self-deterministic universe in the first place. I mean, I was told as a kid that I could be whatever I wanted when I grew up; I was encouraged to think about the kind of man I'd like to marry. But even though we choose the college we go to, the profession we want, or the person we marry (if we actually get the opportunity to make that choice at all), we have no idea, really, of where that choice is going to lead us. I think our life plans, our American self-determination, might be the cover-up for us wildly shooting in the dark.

And while I don't think we all need to go back to believing that superhuman personalities orchestrate the events of our lives, I think the fatalistic understanding might be more accurate in describing the amount of control we actually have.

2.14.2013

A Lot of People

So today Eve Ensler (author/ compiler of The Vagina Monologues) is sponsoring an event called One Billion Rising. I heard about it through her interview on BBC Woman's hour. (Her part starts at 22:50.) It's her response (or rather, one of her responses since she has had many) to the prevalence of violence against women. The UN statistic is that 1 in 3 women and girls will be raped or beaten in their lifetime. This is about 1 billion people.

I took a self-defense class, recently, and they reported the same statistic, only this time specific to the US and submitted by the FBI. My instructor rather understated it when she observed, "That's a lot of people."

That is A LOT of people.

And I'd go on to explain how bad rape is, except that I don't need to because one in six people know first hand.

In her interview, Ensler talks about the world's "absolute acceptance" of rape and of the normalization of violence. She's wondering why we're not in the streets over this stuff.

And, really, why aren't we? It's hard for me to escape the conclusion that there is great apathy towards female lives, that we really don't care about women and girls.

I'm getting worked up. Breathe with me for a second.

...

It's impossible to confront hard things all the time. Hard things are not in front of us all the time. And rape has been with us, has been common, for longer than I want to think about. It takes effort to say, "This isn't right." Or "this needs to change." And what's the point in putting that effort towards a six-billion-people problem that has existed for millennia?

At some point isn't it easier to accept it?

...

There are signs on the inside of the lockers at my gym that say, "Please, do not bring valuables into the locker room. L.A. Fitness is not responsible for lost or stolen items." I think what the signs should say is, "Don't steal things."

We've taken a similar stance on the rape crisis. Our signs say, "Do not bring vaginas onto Earth. If you do, we're not responsible for what happens to them."

...

I was a camp counselor for a week for several summers in high school and college. One year, I had my nine third-grader campers sitting and singing around a camp fire. I started to feel a little sick. One in three. It seemed like a cruel thing for me to let them leave camp.

How do people let us grow up when the statistics are one in three?

It seems like a reasonable response -- maybe even a responsible one -- to decide not to have children because this is the case. Would you let your child move to a country where the murder rate was one in one hundred? (There exists no such country. Although, Maria, your country's pushing it.)

Eve Ensler's One Billion Rising is about dancing sometime, today, to bring awareness and to symbolically throw off the box that rape and the likelihood of rape places on women's bodies. But I'm not sure it's my thing -- as you can see, I'm the defeatist type, crossing my arms, never having kids, and refusing to let my third-graders leave summer camp.

But maybe you're up for it. Seems like a good thing.

Maybe, I'll edit some gym locker signs.

I took a self-defense class, recently, and they reported the same statistic, only this time specific to the US and submitted by the FBI. My instructor rather understated it when she observed, "That's a lot of people."

That is A LOT of people.

And I'd go on to explain how bad rape is, except that I don't need to because one in six people know first hand.

In her interview, Ensler talks about the world's "absolute acceptance" of rape and of the normalization of violence. She's wondering why we're not in the streets over this stuff.

And, really, why aren't we? It's hard for me to escape the conclusion that there is great apathy towards female lives, that we really don't care about women and girls.

I'm getting worked up. Breathe with me for a second.

...

It's impossible to confront hard things all the time. Hard things are not in front of us all the time. And rape has been with us, has been common, for longer than I want to think about. It takes effort to say, "This isn't right." Or "this needs to change." And what's the point in putting that effort towards a six-billion-people problem that has existed for millennia?

At some point isn't it easier to accept it?

...

There are signs on the inside of the lockers at my gym that say, "Please, do not bring valuables into the locker room. L.A. Fitness is not responsible for lost or stolen items." I think what the signs should say is, "Don't steal things."

We've taken a similar stance on the rape crisis. Our signs say, "Do not bring vaginas onto Earth. If you do, we're not responsible for what happens to them."

...

I was a camp counselor for a week for several summers in high school and college. One year, I had my nine third-grader campers sitting and singing around a camp fire. I started to feel a little sick. One in three. It seemed like a cruel thing for me to let them leave camp.

How do people let us grow up when the statistics are one in three?

It seems like a reasonable response -- maybe even a responsible one -- to decide not to have children because this is the case. Would you let your child move to a country where the murder rate was one in one hundred? (There exists no such country. Although, Maria, your country's pushing it.)

Eve Ensler's One Billion Rising is about dancing sometime, today, to bring awareness and to symbolically throw off the box that rape and the likelihood of rape places on women's bodies. But I'm not sure it's my thing -- as you can see, I'm the defeatist type, crossing my arms, never having kids, and refusing to let my third-graders leave summer camp.

But maybe you're up for it. Seems like a good thing.

Maybe, I'll edit some gym locker signs.

2.12.2013

World Geography

I'm surrounded by people who think they know all there is to know about what it means to be an educated person.

A woman in a long, thick dress tells to me the definition of education. She sighs and continues, "I closed my eyes during the presidential election.If Obama didn't win I would've shriveled into a ball for the next four years. Eh, I refuse to be friends with a republican."

I ask her how her homeroom class is going.

She responds, "I don't have my favorite students. They are okay. The kid I hate is gone. He was a poison."

We walk into an old shop classroom. The decrepit gas heater rudely interrupts our conversation. Other teachers are seated around an old clump of tables. A woman drinks diet coke out of a venti-sized Starbucks cup. An intern tries to look important and takes notes. Another teacher stares at the clock. We discuss what we plan to teach the students. The assigned subject is World Geography. A seasoned teacher with a smoky voice confidently announces: "We need to focus our studies on human rights. Let's read Animal Farm. Let's talk about the Holocaust for several weeks. That's world geography. We don't need to teach world history." My thoughts are off with maps, plateaus, earth's atmosphere, and human movement.

"I asked my students a question." Says the woman in the thick dress. "I asked them, if it was legal to cheat, would you cheat on your homework? Two students said they would not. Then I asked the students a question that naturally flows from the previous one: do you consider yourself a good person?"

A woman in a long, thick dress tells to me the definition of education. She sighs and continues, "I closed my eyes during the presidential election.If Obama didn't win I would've shriveled into a ball for the next four years. Eh, I refuse to be friends with a republican."

I ask her how her homeroom class is going.

She responds, "I don't have my favorite students. They are okay. The kid I hate is gone. He was a poison."

We walk into an old shop classroom. The decrepit gas heater rudely interrupts our conversation. Other teachers are seated around an old clump of tables. A woman drinks diet coke out of a venti-sized Starbucks cup. An intern tries to look important and takes notes. Another teacher stares at the clock. We discuss what we plan to teach the students. The assigned subject is World Geography. A seasoned teacher with a smoky voice confidently announces: "We need to focus our studies on human rights. Let's read Animal Farm. Let's talk about the Holocaust for several weeks. That's world geography. We don't need to teach world history." My thoughts are off with maps, plateaus, earth's atmosphere, and human movement.

"I asked my students a question." Says the woman in the thick dress. "I asked them, if it was legal to cheat, would you cheat on your homework? Two students said they would not. Then I asked the students a question that naturally flows from the previous one: do you consider yourself a good person?"

2.11.2013

The National Prayer Breakfast and the PC Police

Mitch showed me this clip from the National Prayer Breakfast of a speech by Dr. Benjamin Carson:

You only need to watch the first six minutes to hear what I'm talking about.

I think it's a mistake to understand political correctness the way he does. He frames it in terms of unanimity and restriction - the idea that political correctness means we need to agree on everything or that we get in trouble for what we talk about rather than how we talk about it.

I agree with him that we need to have conversations - hard conversations. I believe in freedom of thought and speech and the value of saying things that maybe not everybody is going to like. But I don't think political correctness negates this.

Political correctness is essentially public politeness. Its benefits are in letting people participate in a conversation who would traditionally be kept out. It strives to keep personal attacks out of sensitive arguments. It's to broaden conversation rather than restrict it.

I think it's a mistake to blame political correctness for the difficulty in talking about hard or complex topics. The reason it's hard to have conversations about a lot of important things is that a lot of those things are hard. The content makes it uncomfortable, not the PC police.

You only need to watch the first six minutes to hear what I'm talking about.

I think it's a mistake to understand political correctness the way he does. He frames it in terms of unanimity and restriction - the idea that political correctness means we need to agree on everything or that we get in trouble for what we talk about rather than how we talk about it.

I agree with him that we need to have conversations - hard conversations. I believe in freedom of thought and speech and the value of saying things that maybe not everybody is going to like. But I don't think political correctness negates this.

Political correctness is essentially public politeness. Its benefits are in letting people participate in a conversation who would traditionally be kept out. It strives to keep personal attacks out of sensitive arguments. It's to broaden conversation rather than restrict it.

I think it's a mistake to blame political correctness for the difficulty in talking about hard or complex topics. The reason it's hard to have conversations about a lot of important things is that a lot of those things are hard. The content makes it uncomfortable, not the PC police.

2.03.2013

Antigone, Read

Oedipus: Come then, lead me off.

Creon: All right,

but let go of the children.

Oedipus: No, No!

Do not take them away from me.

Creon: Don't try to be in charge of everything.

Your life has lost the power you once had.

-- Sophocles, Oedipus the King

Creon: All right,

but let go of the children.

Oedipus: No, No!

Do not take them away from me.

Creon: Don't try to be in charge of everything.

Your life has lost the power you once had.

-- Sophocles, Oedipus the King

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)